Toward the Future City: An Ethical Design Philosophy for Urban Habitats

Jared Gilbert – COOKFOX Architects

Abstract

Ever taller skyscrapers, increased density, and global interconnectivity are creating new pressures and complexities in both the urban environment and the public space. Contemporary attitudes toward shared environmental and social resources are shifting in response to the challenges of rising inequality, technological connectivity, and global security. Architects are beginning to respond with a heightened sense of ethical obligation to challenge these pressures in pursuit of a design that contributes to the health and well-being of the city, its inhabitants, and its ecology. This paper will discuss global trends in design and planning through the lens of building and project case studies—historic, contemporary, and future—that propose solutions for how the living spaces, workplaces, and shared urban habitats of the future may be designed more ethically by restoring both the foundational ecological systems upon which cities are built and urban connections to nature, creating designs that foster social connectivity and equality.

The 2007 report from the United Nations Population Fund provided a snapshot of our planet in the midst of an astonishingly rapid transformation from a mostly rural to a majority urban population. Much of this migration has happened in the global south, South East Asia, and especially in China. Even in North America urban growth is countering decades-long trends of suburbanization. The world’s cities have pushed buildings taller, increased density, and leveraged technological solutions to manage the social and ecological crises of growth. Yet, technology alone cannot endow society with the qualities that ensure long-term well-being. Design of cities for the future demands a holistic ethical framework that embraces density, diversity and pursues the flourishing of both humans and nature.

Explored through the lens of biophilic design principles and ecosystem functioning, an ethical design philosophy can be developed around the mutually dependent concepts of the flourishing of nature and the flourishing of humanity. Within these concepts are possibilities for addressing challenges of health and well-being in cities, restoring ecological resources, and planning for resiliency in the face of climate change.

Imperative of Biophilic Design

In dense global cities like New York, many urbanites have highly scripted relationships with nature. Wealth, good fortune or privilege affords some with the ability to escape from human-made canyons to windswept beaches or the mountains to reconnect with nature. Many more urbanites experience nature most often in the cracks of decaying infrastructure, tree-pits, and pockets of leftover urban space, and in the formal, bounded settings of city parks that provide local escapes. Whether in privileged enclaves or communal patches of urban green space, social patterns of escape to nature have become embedded in society. However, our connections to nature in our everyday experience of public, working and living spaces are neglected.

Driven by the research of biologists and sociologists, biophilicdesign is emerging as an ethical and moral imperative. We know that humans are mentally and physically healthier when they have direct access to nature. Connection to nature is known to measurably reduce stress and anxiety, improve productivity, and enhance attention and perception. (Terrapin Bright Green 2014) These positive biological responses are not limited to immersive nature experiences, such as walking through a forest. They can also be designed into the urban environment by creating natural analogue conditions that mimic forms and phenomena found in nature. If we know that biophilic design can measurably improve health and well-being, our ethical framework for cities of the future must demand it. Likewise, if we know that our well-being depends on the health of natural systems, our framework must demand that our built environment restore and support ecologies.

In New York, these values are driving a mode of design that is slowly transforming the city—socially and environmentally regenerative architecture and urban design. New architecture is taking on a renewed civic function with renewed purpose to address the most pressing issues of urban places, systemically and locally, in order to affect a healthier, more vibrant city life. One highly visible sign of transformation is in the slow revolution on rooftops, where small patches are becoming green roofs, urban farms, and garden oases. The development of this fifth façade of green space is slowly reknitting urban ecological fabric while improving the health of the city.

Learning from Nature

Cities, like nature, require diversity, balance and restraint to survive. Landscape architect and theorist Ian McHarg wrote, “Human adaptations entail both benefits and costs, but natural processes are generally not attributed values; nor is there a generalized accounting system, reflecting total costs and benefits. Natural processes are unitary whereas human interventions tend to be fragmentary and incremental.” (McHarg 1969) The well-being of a whole ecological system requires an equality of its constituent parts, which are invaluable to the survival of the whole. McHarg advocates that dense urban cores must be designed in concert with open space, and that urban systems should be designed in concert with ecosystems. To develop cities that are in harmony with nature and encourage the flourishing of people, McHarg argues that cities must begin to develop by approaching the unitary mode of nature. Cities must design systemically to halt the forces of fragmentation, such as economic determinism, and create more interdependent and therefore healthier urban spaces.

Our acknowledgement of interdependence is foundational to applying an ethic of human or natural flourishing. Cultural anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson argues that our survival on the planet demands a shift in our relationship to social and ecological systems, breaking from structures of self-sufficiency and adopting structures of mutual dependence. In other words, our individual sense of value and wellbeing must expand to pursue the well-being of the whole of society and of the planet.

Designing with the whole city and ecology in mind requires new ways of planning and developing. New York developer Jonathan F. P. Rose, describes a society of compassion, cooperation and altruism—a transformational ecology—organized to celebrate the interconnectedness of society and nature. His “transformational ecology” requires society to adopt whole systems thinking to refocus our values on collective well-being, and to counter our economic structures that commoditize the individual and component, devaluing the whole. Rose’s transformational ecology depends on healing environmental mistakes of the past for the future well-being of society, cities and planet. The highest potential of our future urban economy and culture is directly tied to the interconnected, mutually dependent flourishing of people and nature. Rose’s 2012 LEED Gold Via Verde development in the South Bronx, one of New York’s most distressed neighborhoods, is one example of his transformational model. The high-rise residential building is mixed-income and mixed-use, with integrated green spaces designed to support the health of residents, including a terraced green roof to host gardening plots for residents and a communal garden that produces over 1,000 pounds of fresh vegetables each growing season. (GrowNYC 2015)

City Point, Brooklyn

City Point, a 1.8 million square foot complex of retail, office, entertainment and high-rise residential buildings in downtown Brooklyn, has become, almost unwittingly, a catalyst for a more vibrant, more diverse urban community. (fig. 1) Having been first designed by COOKFOX Architects just prior to the global financial crisis in 2008, the project was redesigned to fit the new economic realities that demanded renewed consciousness to the needs of the community, focusing on diversity.

The unique site sits at the collision of several Brooklyn street grids and its edges connect with an overwhelmingly diverse collection of neighborhoods and urban uses, from a high-rise corridor of apartment buildings rising along Flatbush Avenue, a large public housing community, a commercial office district, a historic and vibrant retail district, a major university and historic brownstone neighborhoods. The monumental task of the City Point project was to stitch together these fragments, and create a hub of neighborhood services and connector for the full diversity of the community that would anchor the flourishing of downtown Brooklyn.

To accomplish this, COOKFOX created a pedestrian experience that would draw people in and through the building, with a porous streetscape of many entry points, disrupting privileged entries to ensure access for the entire community. The carefully detailed streetscape reinterpreted the scale and proportion of the area’s historic terracotta architecture into a modern expression that complements the weight and warmth of its historic context.

Overhead, the roof of the buildings carries a rich system of gardens, green roof and urban agriculture. While the architecture and planning ties the building to its historic and cultural context, the garden level is a regenerative connector for the urban ecosystem. (fig. 2) Rising from the garden level, two residential towers are arranged to protect the space of the garden and convey a sense of generous openness to the city. Their orientation opens the sky view for pedestrians while providing the necessary high-density, high-rise, multi-income residences to create a diverse, mixed-use community that is socially and ecologically connected.

Ethic of Human Flourishing

In tandem with the green building movement, the architecture world has turned to embrace more socially conscious practices. While building performance will continue to improve with technological advances, designers still have much to accomplish toward healthier, more equitable design.

Architects have always aspired to transform society through design. The early modernists explored radical models of urban living in response to dramatic societal shifts following WWII. New standardized, replicable forms that built on design innovations established between the wars were inspired by the manufacturing industry and made possible by advances in technologies for concrete, glass and building systems. Vast high-rise housing designs reimagined entire neighborhoods as dense vertical communities that would free the land. Despite their environmental and social ideals, these towers, in their quest for efficiency, standardization, and universality were too often disconnected from any sense of history, place or the wider ecology. The technological premise of high-density architecture reached its ultimate conclusion as the late-20th century sealed, tinted glass fortresses that were designed for maximum efficiency, eliminating any outside variability. These towers had the unintended consequence of sealing out nature to the detriment of human well-being.

While the most profound, long-term benefits of holistic, biophilic design for human flourishing may be realized in the urban domestic sphere—homes, schools and hospitals—commercial office buildings have been leading innovation in pursuit of increased productivity and improved mental and physical health for employees. New commercial skyscrapers are being designed as platforms for nature as office tenants demand daylit floor plates, biodynamic lighting, highly filtered air, integrated garden spaces, natural materials and biomimetic patterns to improve human performance. Tall buildings such as 20 Fenchurch Street, London have experimented with new ways of integrating public gardens into buildings for public benefit. Skyscrapers like Shanghai Tower employ whole systems thinking to harnesses ecosystem services of onsite renewable energy and gardens that improve air quality, and improve sustainability and resiliency.

At the other end of the economic spectrum, new affordable and supportive housing is starting to embrace more holistic models to support the well-being of communities. The Hegeman residence, a high-density urban supportive housing project in Brownsville, Brooklyn, was designed to encourage mental, physical and social wellness of its residents. (fig. 3) The stone and brick façade was designed to be clearly modern, but create a sense of permanence for the formerly homeless residents through architecture with weight, a sense of history and relation to the surrounding neighborhood of modest masonry buildings. The apartments are arranged around a garden courtyard, and daylit elevators afford views to the courtyard at every floor, orienting residents to the outdoors. (fig. 4) The direct visual connections to nature, along with tactile qualities of natural materials such as stone and wood, infuse the Hegeman with biological cues that reduce stress and anxiety, and enhance attention and productivity. These biophilic responses are known to improve long-term health and learning, supporting human flourishing with design. To encourage community building between residents and neighbors, the project incorporates a shared community garden in a neighborhood that is starved of arable spaces.

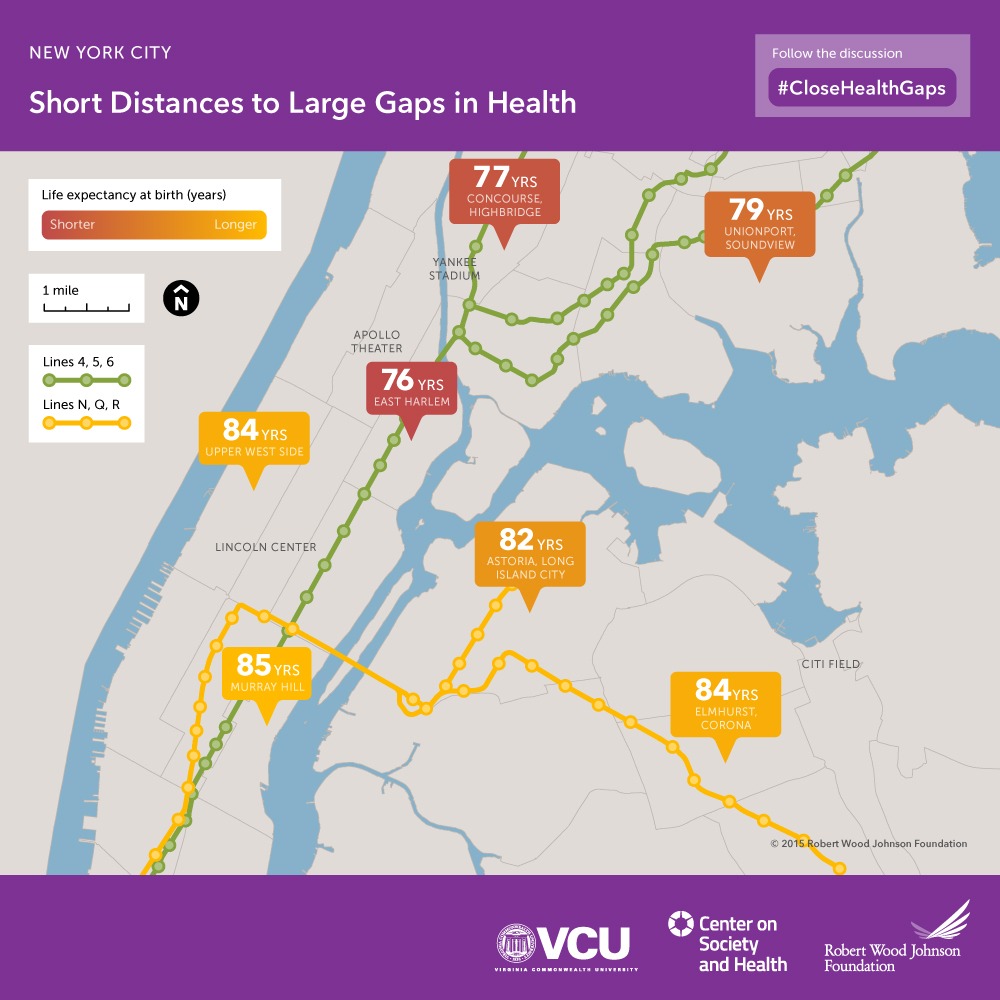

Similar principles are beginning to be explored at the district scale, in an effort to improve the built environment and restore degraded ecologies to improve long-term health outcomes of entire neighborhoods and even cities. In 2013, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released a series of maps illustrating life-expectancy in urban places by transit stop. The astonishing graphics revealed vast differences in life expectancy across relatively small distances. In New York City, a distance of just six subway stops might mean a difference of nearly 10 years. (fig. 5) Economic means is the simplest differentiator between stops; however, community well-being is determined by many gap factors, including quality of housing, education, access to basic services and access to healthy green space. The Foundation’s report entitled, Beyond Health Care: New Directions to a Healthier America, advocates for building healthier communities with solutions that range from policy prescriptions, such as “incorporating health-conscious designs into building codes and zoning,” to design of green infrastructure and healthy buildings for education and living. (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America 2009)

The Foundation helped create a test case that attempted to reverse these gaps. The pilot program took place in Village of East Lake in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, which was one of the poorest, most violent communities in the nation. (Center for Promise Research 2015) The project aimed to transform a neglected stretch of residences with poor environmental factors into a healthy and diverse community. The new development took a whole systems approach, transforming everything from housing to landscape, from schools to supermarkets. The density of the site was doubled by demolishing its 650 sub-quality residences and creating 1,500 mixed-income residences in their place. The residents returned to their reimagined community with new beautiful landscaped spaces for recreation, walkable streets, a daylit school, a diversity of uses and new homes with improved indoor air quality. Within just a few years, health metrics transformed, including a drastic drop in asthma rates, diabetes and heart disease. Area schools went from worst performing to among the best, crime fell dramatically and employment soared. (Schwarz 2015) A community that was dying began to flourish with a simple built intervention to disrupt the patterns of economic determinism with a more ethical design approach.

Some radical urban design solutions are emerging from the developing world that may offer models for the future. Alejandro Avarena, founder of ELEMENTAL, and recent Pritzker Prize Laureate, has introduced a new adaptable housing typology. In pursuit of a financially feasible housing model for marginalized communities, ELEMENTAL’s well-known half-house projects were designed to provide basic shelter needs, while inviting future alternations. (fig. 6) At Quinta Monroy in Iquique, Chile, Avarena worked closely with the poor community living in informal settlements and concluded government subsidies for these families could not pay for right-sized homes. Rather than build smaller homes, Avarena proposed building half a house, or a building that contained the essential spaces of a home—kitchen, bath, a bedroom—and provide the structural frame work for residents to expand and modify their home over time to accommodate growing families or add space for working, a concept that is common in informal settlements. Avarena’s goal is no less ambitious than overcoming poverty with safe adaptable homes as a platform for families to flourish. ELEMENTAL reports that many of the homes doubled in value in just a year, giving poor families an important boost out of poverty. (Tory-Henderson 2016) Avarena’s design provides a framework for human flourishing and the model is proving to be replicable in urban places. The firm completed similar projects in Constitución, Chile, and Monterey, Mexico. A future designer may be inspired by the vertical informal settlement, such as once existed at “Torre de David” in Caracas, Venezula, and develop a “half skyscraper” system designed to be safe, adaptable and inspire innovation.

Ethic of Ecological Flourishing

With the ethical concept of human flourishing established, we turn to its symbiotic concept, that of ecological flourishing. In his essay “Living by Life: Some Bioregional Theory and Practice,” activist Jim Dodge writes, “the health of natural systems is directly connected to our own physical/psychic health as individuals and as a species, and for that reason natural systems and their informing integrations deserve, if not utter veneration, at least our clearest attention and deepest respect.” (Dodge 2007) In the face of climate change, repairing our ecologies is vital, not only for preserving our basic essential resources of water, clean air and arable land, but also for healthy human biological functioning.

At the penthouse level of 641 Avenue of the Americas in New York City, a grim rooftop was transformed into a haven for natural life. Where disused and rusting mechanical equipment once sat, a teaming micro-ecosystem has taken hold. (fig. 7) The green roof, installed and maintained by COOKFOX staff, was started with six species of sedum and allowed to evolve with the fortuitous introduction of volunteer plants. The green space has become a haven for birds and bugs, including American Kestrel hawks that regularly hunt on the rooftop. Located in one of the most ecologically barren and dense parts of Manhattan, the garden is a small restorative effort designed for environmental flourishing. Extending from the workspace, the garden is visible from nearly every desk and is a constant connection to nature and natural cycles that promotes improved attention, reduced stress and higher productivity. The roof also hosts an experimental urban farming project, creating opportunities for the staff to grow food and interact directly with soil and plants to understand the possibilities for micro-scale urban food production. (fig. 8)

With a clear view from my own workstation, I am energized by observing the green roof during moments of respite throughout the work day. The experience of witnessing nature thrive has become deeply personal and a powerful symbol for the possibilities of transforming the city into a healthier, more just and verdant ecology of people and nature.

Ethic of Ecological Flourishing

With the ethical concept of human flourishing established, we turn to its symbiotic concept, that of ecological flourishing. In his essay “Living by Life: Some Bioregional Theory and Practice,” activist Jim Dodge writes, “the health of natural systems is directly connected to our own physical/psychic health as individuals and as a species, and for that reason natural systems and their informing integrations deserve, if not utter veneration, at least our clearest attention and deepest respect.” (Dodge 2007) In the face of climate change, repairing our ecologies is vital, not only for preserving our basic essential resources of water, clean air and arable land, but also for healthy human biological functioning.

At the penthouse level of 641 Avenue of the Americas in New York City, a grim rooftop was transformed into a haven for natural life. Where disused and rusting mechanical equipment once sat, a teaming micro-ecosystem has taken hold. (fig. 7) The green roof, installed and maintained by COOKFOX staff, was started with six species of sedum and allowed to evolve with the fortuitous introduction of volunteer plants. The green space has become a haven for birds and bugs, including American Kestrel hawks that regularly hunt on the rooftop. Located in one of the most ecologically barren and dense parts of Manhattan, the garden is a small restorative effort designed for environmental flourishing. Extending from the workspace, the garden is visible from nearly every desk and is a constant connection to nature and natural cycles that promotes improved attention, reduced stress and higher productivity. The roof also hosts an experimental urban farming project, creating opportunities for the staff to grow food and interact directly with soil and plants to understand the possibilities for micro-scale urban food production. (fig. 8)

With a clear view from my own workstation, I am energized by observing the green roof during moments of respite throughout the work day. The experience of witnessing nature thrive has become deeply personal and a powerful symbol for the possibilities of transforming the city into a healthier, more just and verdant ecology of people and nature.

Survival Design

The density, verticality and creative collisions of cities provide rich ground to design for flourishing of humans and nature. By virtue of their scale and capital, mega-projects, such as super-tall skyscrapers, are able to affect market transformation for healthier environments, and in more ecologically integrated buildings, architects, engineers and developers can push innovation and develop new whole-systems models for development.

It has often been noted that the first skyscrapers were not banks and corporate headquarters, rather they were shared monuments in the form of cathedrals, temples and public monuments. These great constructions, often created over generations by a whole community of labors and supported by entire cities, were the economic, social and creative lifeblood of the societies that built them. The remarkable urban transformation projects that have captivated New York City—the High Line, Hudson Yards, World Trade Center—all have a common feature of open, green space. These public spaces are the cathedrals, temples, and monuments of our modern city. While thousands of workers sit in towers above, many more thousands will experience these places as public gathering places, infused with nature. Besides these highly designed spaces, few projects in New York have had as much impact on community life as tactical urbanism that has turned vehicular streetscapes into pedestrian areas and oases of planted space. These small discrete actions to pursue a new vision for urban design have transformed the city. For the survival of cities, architects, engineers and developers must adopt a kind of tactical design to begin to transform our skyscrapers and streets to support the well-being of our entire city, creating spaces for the flourishing of humans and ecology.